MNI: RBA November Cut Eyed, Lower Productivity To Pull Down R*

The Reserve Bank of Australia is likely to hold at its September meeting before delivering another 25-basis-point cut to the 3.6% cash rate in November, former staffers and leading economists told MNI, with the Bank’s downgraded productivity outlook expected to weigh on neutral rate estimates over the longer term.

Andrew Barker, senior economist at the Committee for Economic Development of Australia and a former OECD economist, said this week’s upside surprise in the monthly inflation indicator would be enough to keep the cautious board on hold until quarterly CPI arrives ahead of the Nov 3–4 meeting, where markets are pricing about an 80% chance of a cut.

“It does look like there's something other than just the end of the electricity rebates going on there,” Barker said of Wednesday’s release, which showed the trimmed mean rising 60bp to 2.7% in July. “So probably expecting one more cut by the end of the year. But with lower productivity, the neutral rate is likely a little bit lower. One more cut would still be above the neutral rate, so it depends a lot on what happens to global growth.”

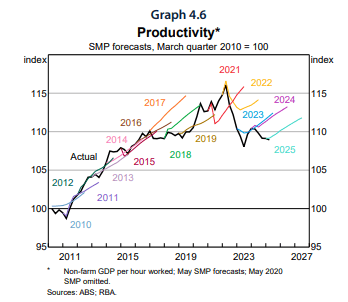

Barker said the Bank’s downgrade of its productivity growth outlook earlier this month would pull down its estimate of r-star and open the way to lower rates over the longer term. (See MNI RBA WATCH: Bullock Points Toward Further Cuts) “We’ve had weak productivity growth for almost 10 years, so this is definitely going to be pushing down the neutral rate,” said Barker, who is also a former Productivity Commission economist.

PRODUCTIVITY MISSES

Luke Hartigan, University of Sydney lecturer and former RBA economist, said the revision was welcome but suggested it raised questions over whether policy had been kept too tight in hindsight. “If you look at the inflation outcomes, it’s broadly now in target. So maybe it wasn’t an issue, but it does open the question… maybe policy was tighter than needed,” he said, pointing to evidence in the RBA’s own review showing misjudgments of potential growth. (See chart)

"Maybe this is one of the reasons why inflation was too low going into the [pandemic] crisis – maybe policy was too tight then.”

Hartigan noted lower productivity would show up in wage dynamics. “The speed limit of the economy is lower. All else equal, wages can’t rise as fast as before… So it would mean that the economy won't be able to get as much momentum for policy to be tightened again.” He expects the RBA to cut in September, noting that the central bank paid little attention to the monthly indicator and that Governor Michele Bullock and recently-published minutes from the August meeting showed a clear easing bias.

John Hawkins, professor at the University of Canberra and former RBA economist, agreed weaker productivity would weigh on star variables. “In theory, if you think productivity is lower, you’d think r-star is lower,” he said. “It would also change their view on what’s a sustainable rate of wage growth. Where you might have thought wages could average 3.5%, now you’d be thinking closer to 3.2% would be consistent with the inflation target.”

Hawkins saw a November cut as the most likely outcome given the Board’s preference for quarterly inflation data, adding that one more reduction after that would bring policy settings close to neutral. He also flagged risks from abroad, warning the Bank appeared “complacent” on global trade. “They seem to be assuming things won’t move into the worst-case scenario they modeled a few months ago," he said, pointing to scenarios the bank published in May that showed significant economic growth risk due to U.S. trade policy. (See chart)

"Most countries have just grumbled about Trump’s tariffs rather than retaliating, but that’s still a risk,” he said.